Dan Houser on Zelda: Breath of the Wild & Tears of the Kingdom – A Masterclass in Video Game Storytelling

Gaming News is thrilled to present an in-depth exploration into the profound insights offered by Dan Houser, the acclaimed co-founder of Rockstar Games, regarding Nintendo’s seminal Zelda titles, specifically The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and its monumental successor, Tears of the Kingdom. Houser, a visionary architect behind some of the most compelling and immersive narrative experiences in interactive entertainment, likens these Nintendo masterpieces to the timeless works of Alfred Hitchcock, praising their inherent ability to communicate narratives and evoke emotions through the unique and uniquely video game medium. His perspective offers a fascinating lens through which to appreciate the artistry and innovation embedded within these critically acclaimed open-world adventures, solidifying their status as landmark achievements in game design and interactive storytelling.

The Hitchcockian Parallel: Suspense, Atmosphere, and Purely Interactive Expression

The comparison between Zelda: Breath of the Wild, Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, and the cinematic legacy of Alfred Hitchcock is not merely a superficial observation; it delves into the very core of what makes these experiences so compelling. Hitchcock, often dubbed the “Master of Suspense,” was renowned for his ability to build tension, create palpable atmosphere, and manipulate audience emotions through visual storytelling, pacing, and psychological depth. Houser suggests that Nintendo, in crafting these Zelda games, has achieved a similar mastery, but within the distinct confines of video game language.

This “language of video games,” as Houser terms it, is not about simply translating cinematic techniques but about leveraging the interactive nature of the medium to its fullest potential. Unlike a film, where the viewer is largely passive, a player in Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom is an active participant. Every choice, every exploration, every interaction contributes to the unfolding narrative and the player’s emotional connection to the world of Hyrule. This is where the Hitchcockian influence truly shines. The suspense isn’t necessarily born from jump scares or overt threats, but from the player’s intrinsic curiosity, the vastness of the unknown, and the subtle environmental cues that hint at dangers and secrets.

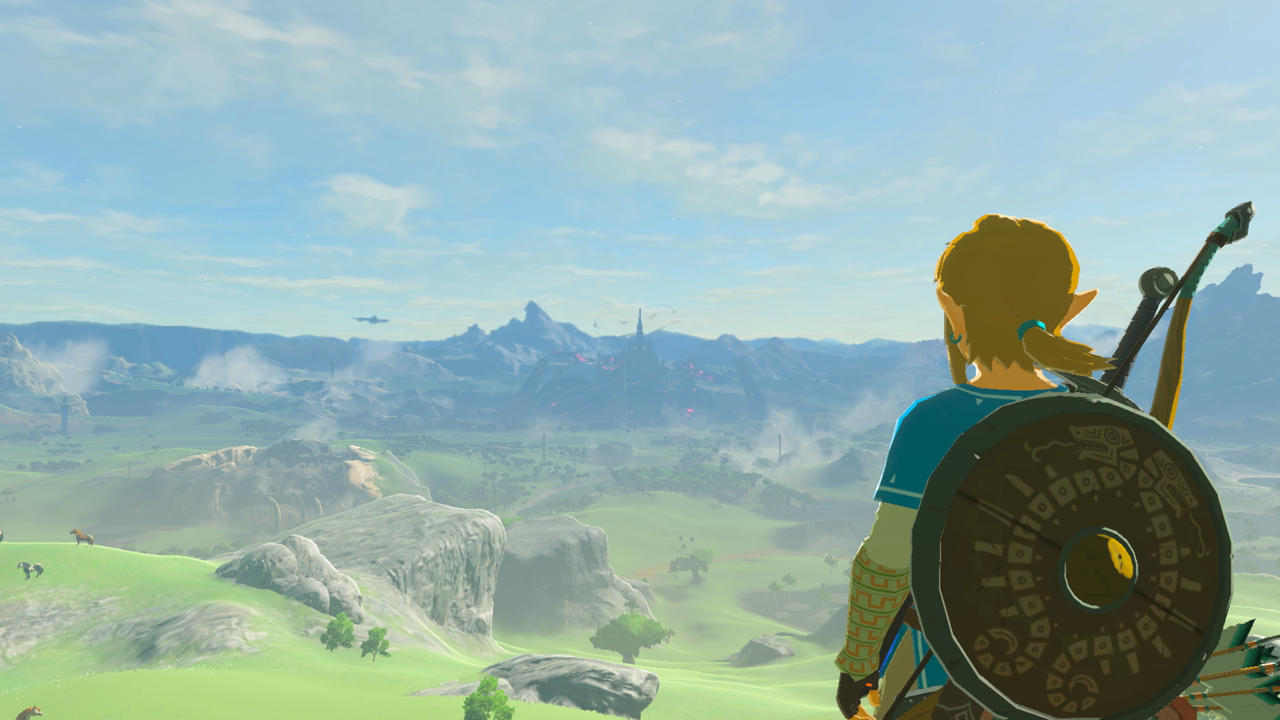

We can observe this in the meticulous environmental design of both games. The towering cliffs, the rustling grass, the distant calls of unseen creatures – these elements, when combined with the player’s limited initial knowledge and resources, create a sense of vulnerability and anticipation that mirrors the suspense Hitchcock masterfully wove into his films. The games are not just presenting a story; they are inviting the player to experience a story, where their agency is paramount.

“These Amazing Things That Could Only Be Video Games”: Defining Interactive Uniqueness

Houser’s assertion that Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom are “these amazing things that could only be video games, they couldn’t be anything else” is a powerful statement about the medium’s unique potential. It signifies a rejection of the notion that video games are merely a less sophisticated cousin to film or literature. Instead, Houser elevates them to an art form with its own distinct vocabulary and expressive capabilities.

The core of this argument lies in the concept of player agency and the emergent gameplay that arises from it. In Breath of the Wild, for instance, the freedom to approach any objective from any angle, to experiment with physics-based puzzles, and to forge one’s own path across Hyrule is something that no other medium can replicate. The sense of discovery is not pre-scripted; it is organic and player-driven. When a player devises a clever solution to a puzzle using an unexpected combination of items and abilities, or when they stumble upon a hidden shrine through sheer exploration, that experience is uniquely theirs. It is a narrative consequence of their interaction with the game world, not merely a predetermined plot point.

Tears of the Kingdom further expands upon this foundation, introducing the revolutionary Ultrahand and Fuse abilities. These mechanics empower players to construct elaborate contraptions, fuse weapons with elemental properties, and solve problems in ways that were previously unimaginable. The sheer breadth of creative possibilities that these tools unlock ensures that each player’s journey through Hyrule is profoundly personal and distinct. The emergent narratives that arise from these player-created solutions – the whimsical flying machines, the Rube Goldberg-esque traps, the creatively fused weapons – are testaments to the fact that these experiences are fundamentally video games. They cannot be translated into a passive viewing or reading experience without losing their essential magic.

Houser’s perspective suggests that the true brilliance of these Zelda titles lies in their ability to leverage interactivity to create emotional resonance and narrative depth in ways that are singular to the medium. The joy of discovery, the frustration of a failed experiment, the triumph of overcoming a seemingly insurmountable challenge – these are all heightened by the player’s active involvement. This is the language of video games speaking, and Nintendo has proven to be one of its most eloquent practitioners.

The Art of Environmental Storytelling in Hyrule

One of the most significant contributions of Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom to the landscape of interactive storytelling is their masterful application of environmental storytelling. This is an area where the Hitchcockian parallel becomes particularly potent. Hitchcock understood that setting, mise-en-scène, and subtle visual cues could convey as much, if not more, than direct dialogue. Nintendo has taken this principle and infused it into the very fabric of Hyrule.

In Breath of the Wild, the ruined villages, the ancient Shiekah technology scattered across the land, and the weathered remnants of past battles all speak volumes about the history and current state of Hyrule. Players don’t need explicit exposition dumps to understand that a great calamity has befallen the land. The world itself tells the story. The wind whistling through empty structures, the skeletal remains of guardians, and the forlorn diaries left behind all contribute to a rich tapestry of lore that players can uncover at their own pace. This approach fosters a deep sense of immersion, allowing players to piece together the narrative through observation and exploration, much like a detective unraveling a mystery.

Tears of the Kingdom builds upon this foundation with even greater sophistication. The addition of the Sky Islands and the Depths introduces entirely new biomes, each with its own distinct history, secrets, and narrative implications. The Zonai ruins, the ancient murals, and the geological formations all offer clues to the origins of the Zonai civilization and their connection to the current crisis. The developers have meticulously crafted these environments to evoke specific moods and convey information implicitly. The oppressive darkness of the Depths, for instance, creates a palpable sense of dread and danger, while the serene beauty of the Sky Islands hints at a lost paradise.

This dedication to environmental storytelling is precisely what makes these games so “only video games.” The player is not merely told about the world; they are allowed to inhabit it and discover its secrets through their own exploration. The act of climbing a mountain to survey the landscape, of venturing into a dark cave, or of deciphering an ancient glyph becomes an integral part of the narrative experience. This is a form of storytelling that relies on visual cues, spatial awareness, and player deduction, all of which are hallmarks of interactive engagement.

Leveraging Player Freedom for Narrative Impact

The unparalleled player freedom offered in Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom is not just a gameplay mechanic; it is a crucial narrative tool. Houser’s observation that these games speak the language of video games is directly tied to how this freedom allows for personalized narrative arcs.

In Breath of the Wild, the open-ended nature of the quest design means that players can tackle the main story objectives in almost any order. This allows for a highly individualized experience. A player who prioritizes exploring the vastness of Hyrule might discover crucial lore or obtain powerful gear before even confronting a Divine Beast. This organic progression of knowledge and capability shapes their perception of the narrative and their emotional investment in Link’s journey. The sense of accomplishment derived from overcoming a challenge through self-discovery and clever planning is a potent narrative driver that is unique to the interactive medium.

Tears of the Kingdom elevates this concept with its more complex and interconnected world. The ability to traverse the skies, delve into the depths, and explore Hyrule from multiple vertical layers creates an even richer tapestry of potential player experiences. The introduction of Hyrule’s history through the Dragon Tears further emphasizes the player’s role as an active archaeologist. The order in which players discover these memories, and the context in which they encounter them, can profoundly influence their understanding of the events leading up to the current cataclysm and the motivations of its key figures. This player-driven discovery of lore creates a more profound and personally resonant narrative than simply being presented with cutscenes.

The Hitchcockian element here lies in the suspense of the unknown. Because players can explore freely, they are constantly encountering new environments, new challenges, and new pieces of the narrative puzzle. This creates a sense of anticipation and curiosity, mirroring the way Hitchcock would build tension through unresolved questions and looming threats. The games trust the player to engage with the world and its stories, fostering a sense of ownership over the narrative that is uniquely powerful in video games.

The Power of “Show, Don’t Tell” in Interactive Design

A cornerstone of effective storytelling across all mediums is the principle of “show, don’t tell.” Dan Houser’s admiration for Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom highlights how effectively Nintendo employs this philosophy within the language of video games.

Instead of lengthy expositional dialogue explaining the history of Hyrule or the nature of Ganon’s malice, Nintendo presents players with visual evidence. The crumbling architecture, the ancient murals, the spectral echoes of past events – these are all narrative elements that players actively discover and interpret. This approach not only respects the player’s intelligence but also fosters a deeper engagement with the world. The player feels like an investigator, piecing together clues rather than being passively fed information.

Consider the introduction of the Zonai in Tears of the Kingdom. Their presence is revealed not through lengthy speeches but through their architectural marvels scattered across the sky and their technological remnants. The player encounters their legacy through exploration, observation, and interaction with their creations. The Sages’ stories, delivered through interactive flashbacks triggered by the Dragon Tears, are powerful precisely because they are woven into the gameplay and presented as discovered memories, not as linear plot points. This “showing” of history through interactive discovery is a testament to the medium’s capabilities.

This aligns with Hitchcock’s mastery of visual storytelling. He would often convey character emotions, plot points, and thematic elements through camera angles, set design, and the actors’ subtle performances. Nintendo achieves a similar effect by using the interactive environment and gameplay mechanics as their primary storytelling tools. The satisfaction derived from solving a complex puzzle through experimentation, or the thrill of discovering a hidden cave filled with lore, are direct manifestations of the “show, don’t tell” principle within the uniquely video game context. This is what makes these titles so revolutionary in game design.

Beyond Imitation: The True Language of Video Games

Dan Houser’s pronouncements serve as a vital reminder that the most impactful video games are not those that merely imitate other mediums, but those that fully embrace and explore the unique language of video games. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom stand as prime examples of this philosophy in action.

Their success lies in their ability to weave intricate narratives, evoke profound emotions, and create unforgettable experiences through interactivity, exploration, and emergent gameplay. The Hitchcockian parallels highlight their mastery of suspense and atmosphere, but it is their purely interactive expression that truly sets them apart. They demonstrate that video games can be a powerful and sophisticated medium for storytelling, capable of delivering experiences that are uniquely engaging and deeply personal.

As we continue to witness the evolution of interactive entertainment, the lessons learned from these Nintendo masterpieces, and the insights offered by visionary creators like Dan Houser, will undoubtedly continue to shape the future of game design and interactive storytelling. The profound impact of Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom solidifies their place not just as great games, but as landmark achievements in the art form that are truly uniquely video games. Their influence on open-world game design and narrative innovation is undeniable, pushing the boundaries of what players can expect and experience. The Gaming News team believes that the legacy of these games will continue to inspire developers for generations to come, setting a new benchmark for interactive narratives.